The Beast of Gévaudan: the shocking legend France still can’t explain

Imagine you’re pottering about the hills, sheep in tow, when a blood-curdling rumour slouches out of the forests in the foggy wilds of south-central France, circa 1764. The now-famous “Beast of Gévaudan” is loose! For folks in the then-province of Gévaudan, the summer promises no sunlit picnics, but the thrumming anxiety of a mysterious, murderous creature stalking the landscape.

A monster made for nightmares

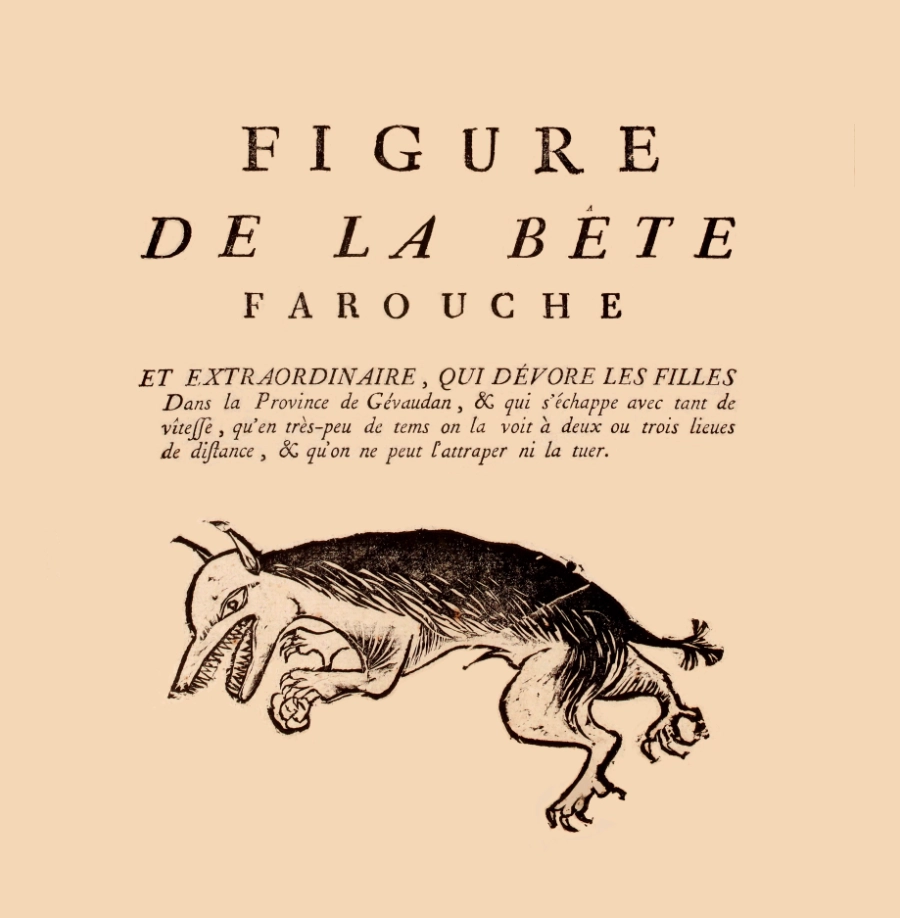

You see, this wasn’t your average big sheep-worrying wolf, nor was it the neighbour’s dog gone rogue. Eyewitnesses were adamant: the beast was “as big as a calf” (sometimes a donkey, French embellishment knows no bounds), with russet fur streaked like a dodgy dye job, a tail longer than reason, teeth and claws fit for ripping through your worst Sunday roast nightmares, and a face no mother could love. Terrified villagers swore up and down that it bounded across fields with an ungodly leap and preferred attacking women and children, especially little girls.

How many fell victim? The numbers, like the best fish stories, vary depending on who’s telling it. Some whisper of at least 210 attacks with over a hundred deaths, many so brutal that only bones were left, a detail that, for full effect, should probably be shared long after pudding is served

The burial record for Jeanne Boulet

One of the earliest encounters: a young woman minding cattle near Langogne spots a creature “like a wolf, yet not a wolf.” Minutes later, rather heroically, the herd’s bulls charge at the beast, sending it scampering. That’s French livestock for you, not ones to stand idly by whilst supernatural weirdness unfolds.

Sadly not everyone was so lucky. On June 30th, 1764, tragedy struck. Fourteen-year-old Jeanne Boulet became the first recorded victim, attacked and killed near Les Hubacs. Her burial record, noting “the ferocious beast,” marks the official start of three years of terror that would reshape the region’s psyche forever.

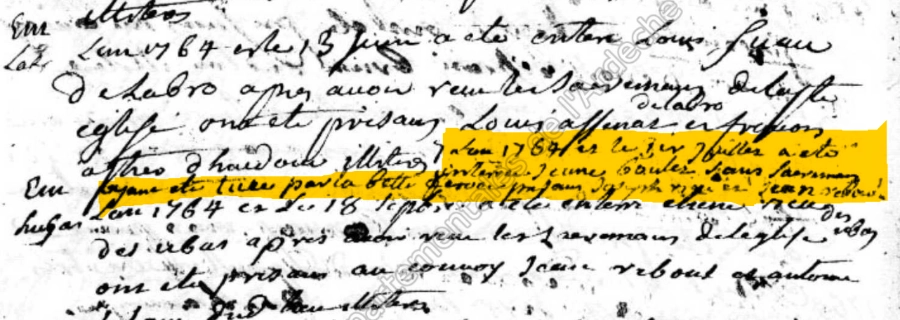

The burial record for Jeanne Boulet, written in the parish register of Saint-Étienne-de-Lugdarès from 1 July 1764s, reads:

“L’an 1764 et le 1 Juillet, a été enterrée, Jeane BOULET, sans sacremens, ayant été tuée par la bette féroce, présans Joseph RIEU et Jean REBOUL.”

“In the year 1764, on 1 July, was buried Jeanne Boulet, without sacraments, having been killed by the ferocious beast, in the presence of Joseph Rieu and Jean Reboul.”

Death certificate of Jeanne Boulet. July 1, 1764. © Departmental Archives of Ardèche, St Étienne-de-Lugdarès.

Hunting parties, heroic children, and a king’s intervention

Soon enough, the story drew more than local headlines, it made its way into national newspapers and, as you’d expect from any good monster tale, across the Channel to London. Sensational stories whipped through the press, and the king himself, Louis XV, threw in his lot, dispatching elite hunters and offering a bounty fit for a small estate.

Soldiers, noblemen, and ambitious local hunters tracked the beast through wild forests, armed with guns, sabres, and bloodhounds. Even local children got involved, like young Jacques Portefaix, who rallied his mates to pelt the creature with stones and rudimentary weapons, fending it off long enough for their tale of courage to reach Versailles. Louis XV, clearly impressed and perhaps a sentimental old soul, funded their education at state expense.

All the while, Gévaudan’s economy ground to a halt. Shepherds refused to graze their flocks, fields went untended, hunger spread, and markets dried up along with community morale. Fear wasn’t simply beneath the bed, it was out in the fields, disrupting the rhythm of daily life.

Marie-Jeanne Vallet, the Maid of Gévaudan

This is where the story gets its heroine. On 11 August 1765, nineteen-year-old Marie-Jeanne Vallet became the stuff of legend. Out with her sister near Paulhac-en-Margeride, she found herself face-to-face with the infamous beast. Did she panic? Not a chance. Armed only with a bayonet fixed to a stick, Marie-Jeanne stood her ground as the beast charged. With unflinching nerve, she struck it in the chest, wounding it deeply enough to make it howl and flee to lick its wounds.

Her story spread quickly; soon she was dubbed “La Pucelle du Gévaudan”, the Maid of Gévaudan, a rare voice of hope in an otherwise grim saga. Louis XV’s official huntsman even verified the wound. While the beast wasn’t finished, the people of Gévaudan had found new courage in Marie-Jeanne’s defiance. Today, a statue in Auvers honours her bravery: not every legend gets a monument, but then, not every legend earns it quite so spectacularly.

The Beast of Gévaudan’s many lives: myths, monsters, and medical mysteries

Newspapers had a field day with the carnage. Reports described the beast variously as a giant wolf, a striped hyena (in rural France?), a bloodthirsty lion, or some hybrid monster with lurid red and black fur, outlandish stamina, and a penchant for theatrical violence. Some swore it walked on its hind legs, dodged bullets, and, as if written by a copy editor on deadline, could not be killed, only delayed.

Even autopsies failed to pinpoint a culprit. When François Antoine slew a large wolf in 1765 and paraded the corpse for Versailles, he basked in royal glory, until the murders resumed, gods forgive him. It took Jean Chastel, local chap, to finally finish the deed during a hunt led by the Marquis d’Apcher on 19 June 1767. The attacks ceased, at last, but the mystery… well, it only deepened.

Folklore grows: where horror meets humanity

The aftermath is testament to the power of rumour and communal storytelling. The legend lived on. If you’d wandered into a local inn a century later, you’d still find the beast rearing its ugly head in stories told round the fire. Artists illustrated it as big as a young bull, with claws, pointy ears, and a tail “mobile like a cat’s.” Victims’ heads lopped clean off, their blood drained, a macabre fairytale for cold winter nights.

Over time, the beast became a mirror reflecting society’s deepest anxieties: about the wild, the untamed, and the limits of rational authority. Was it a supernatural thing? Man masquerading as beast? Or just a very mischievous beastly bugger with a taste for drama? The quest to answer that question has inspired novels, films, local festivals, and the occasional village prank ever since.

Beast of Gévaudan as a symbol: more than fur and fangs

For the people of Gévaudan (and let’s be honest, all of France), the beast wasn’t merely a predator, it was a living, snarling reminder of life’s unpredictability. It upended order, mocked authority, and brought communities together in shared terror and dogged resistance.

Its legend still stalks the French cultural imagination. The museum of Gévaudan in Lozère, pubs in London, and haunted trail enthusiasts all keep the beast’s story alive, not for the sheer horror, but for the way it draws us together round a shared fire, sparking questions that have no tidy answers. Perhaps our fascination with monsters, whether furry or otherwise, is just another way of confronting what we don’t quite understand. The beast, after all, is as much a part of humanity as the heroes who stood up to it.

The joy of the unknown

So, what have we learned from the beast, apart from the obvious (don’t graze sheep in suspicious forests and never trust a creature described as “red and black with a cow’s tail”)? Maybe it’s that history, like good legend, isn’t just a list of dates and gruesome endings. It’s a living tapestry, woven from fear, resilience, gossip, and, dare I say, a touch of French bravado.

If you’re ever planning a trip through Lozère, keep one eye on the misty hills and another on the nearest villager’s storytelling prowess. You might just catch echoes of the beast in local festivals, wild-eyed art, or the knowing laughter of someone who wasn’t entirely convinced by the autopsy results.

If you fancy a pint while reflecting on what keeps us up at night, the beast of Gévaudan’s legacy is safe: a reminder not to take life, or legend, too seriously. Because sometimes, facing the unknown with a grin and a story to tell is just what we need to keep moving, together, across fields dark and light.

Beast: Werewolves, Serial Killers, and Man-Eaters

If you want the full story and all the wild rumours behind the beast of Gévaudan, this book does the job. It’s direct, packed with proper history and the sort of gritty detail that brings old French legends to life. Perfect if you like your folklore with a good dose of truth and a bit of bite.

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably as drawn to the mystery as any villager of old Gévaudan. Have you got a favourite monster tale, or maybe a theory about what really lurked in those French woods? Jump into the comments!