Saint-Gaultier

A river town on the edge of La Brenne

Saint-Gaultier sits on the banks of the Creuse in the Indre, about 15 kilometres from Argenton-sur-Creuse. It’s a town of 1,800 people that most visitors drive straight past on the A20, which is rather a shame. This medieval riverside town has a proper Romanesque church, bits of fortification poking out of back gardens, and sits at the gateway to the Brenne Regional Natural Park, the so-called “land of a thousand lakes.”

The town’s named after Gaultier, an 11th-century abbot from Lesterps who founded a priory here around 1060. What started as a religious settlement became a fortified town that answered directly to the Vatican, which gave it protection during the Hundred Years’ War and the Wars of Religion. More usefully, it also gave Saint-Gaultier the right to charge tolls on its bridge over the Creuse, making it one of the few French towns paid by the papacy in gold florins, the international currency of the time.

These days it’s quieter. A small town where the most excitement comes from the weekly market and the occasional punaise de colza invasion (ask the locals about 2019). But if you’re heading south through the Indre, or if you want a base for exploring the Brenne without staying in the middle of nowhere, Saint-Gaultier’s worth more than a motorway glance.

The church and priory

The church of Saint-Gaultier dominates the riverside skyline, and you get the best view of it from the old railway viaduct that’s now part of the “voie verte”. It’s a substantial Romanesque church built in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, which sounds a bit grand for what was then a small priory town.

The church shows influences from both Limousin and Poitou, the neighbouring regions that have always argued over this bit of the Indre. Square pillars, a dome, barrel vaults on pillars with carved capitals showing allegorical figures. The portal’s Romanesque-Poitevin style, without a tympanum, which apparently matters if you’re into church architecture.

Round the back, the chevet has modillions and capitals with scenes from the Roman de Renart, that medieval fox tale everyone read in the 12th century. Look for the donkey playing the lyre in front of a hurdy-gurdy man. Medieval stonemasons had a sense of humour.

The priory attached to the church became a college in 1740, then a seminary thirty years later. Now it’s the local secondary school. You can see the southern facade from the road, including the chapel, built between 1868 and 1884. The architect partly reused earlier constructions, so bits of the medieval priory are still lurking in there amongst the 19th-century additions.

What’s left of the fortifications

Saint-Gaultier was a walled town, and if you poke around the back gardens along the Creuse you’ll spot remnants of ramparts and towers. The town had protection thanks to its direct link to the papacy, convenient during the Hundred Years’ War when English troops were tramping about the region.

The wealth came from that toll bridge over the Creuse. Rivers were the main transport routes in medieval times, and controlling a crossing meant controlling trade. The bridge itself has had a rough history. In 1530 a badly damaged bridge was washed away entirely by the river. They finally rebuilt it in 1654. Then the Creuse destroyed it again, leaving only ruins of a pile in the river. Around 1830 they built a suspension bridge, which lasted until 1878 when the current bridge replaced it.

Rue du Cheval Blanc commemorates Henri IV’s visit in March 1589. One tower supposedly housed Good King Henry during his stay, though why he was in Saint-Gaultier in the middle of the Wars of Religion isn’t entirely clear from the local histories.

The Voie Verte and the Creuse

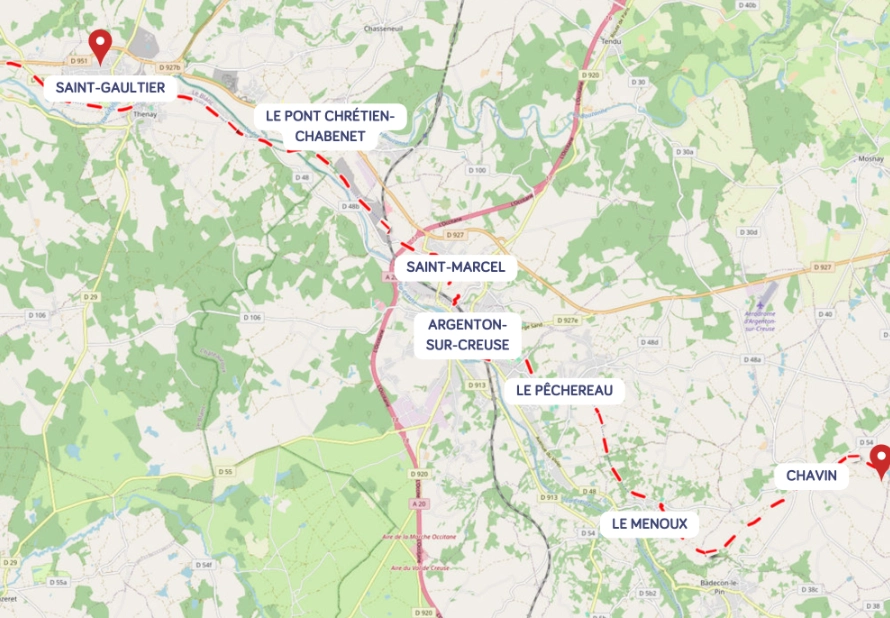

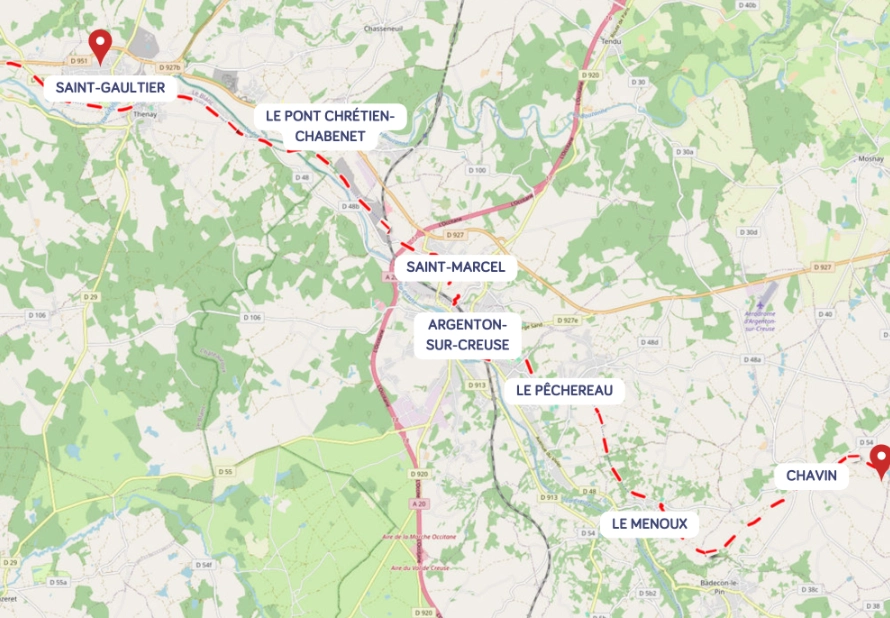

The old railway line from Argenton-sur-Creuse to Le Blanc has been converted into a “voie verte”, a traffic-free greenway for cycling, walking, and the occasional horse. It runs right through Saint-Gaultier, crossing the Creuse on the old viaduct.

From Saint-Gaultier you can cycle north towards Argenton-sur-Creuse, about 15 kilometres along the river valley. South takes you deeper into the Brenne and towards Le Blanc. The route’s well-marked, with the occasional picnic bench and information panel about local wildlife.

Walking or cycling

This greenway passes through countryside, fields, orchards, the odd hamlet, woods. In spring and early summer it’s lovely. In high summer it can get hot, so bring water! In autumn you’ll see flocks of migrating birds heading to the Brenne’s lakes.

This is a flat and easy route, perfect for families or anyone who wants to cycle without the terror of French drivers. The surface is good, the gradients gentle (this is the Indre, not the Alps), and you get river views without having to share the road with agricultural machinery.

Several walking routes start from Saint-Gaultier itself, including a historical circuit that covers the town’s heritage and then climbs to the heights for views over the Creuse valley. The tourist office has maps, or you can download routes from Visorando if you want more options.

Saint-Gaultier’s industrial empire: the lime kilns

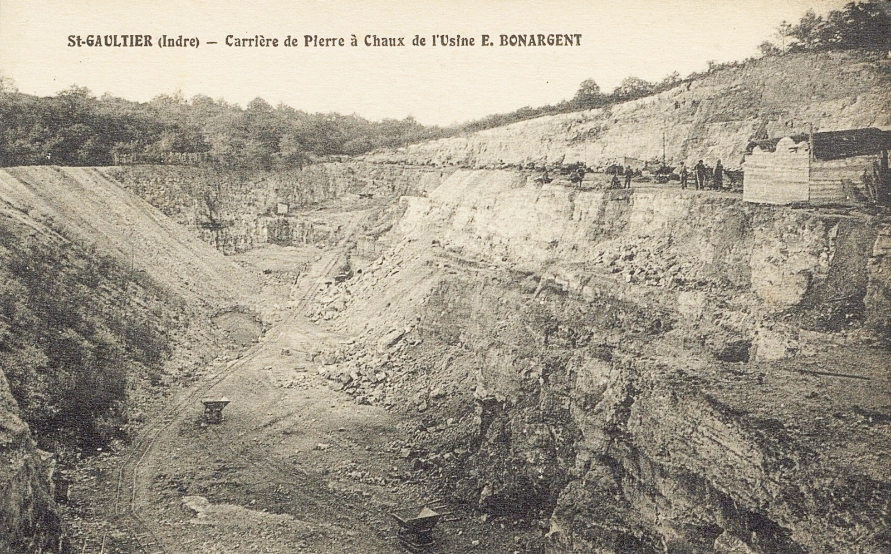

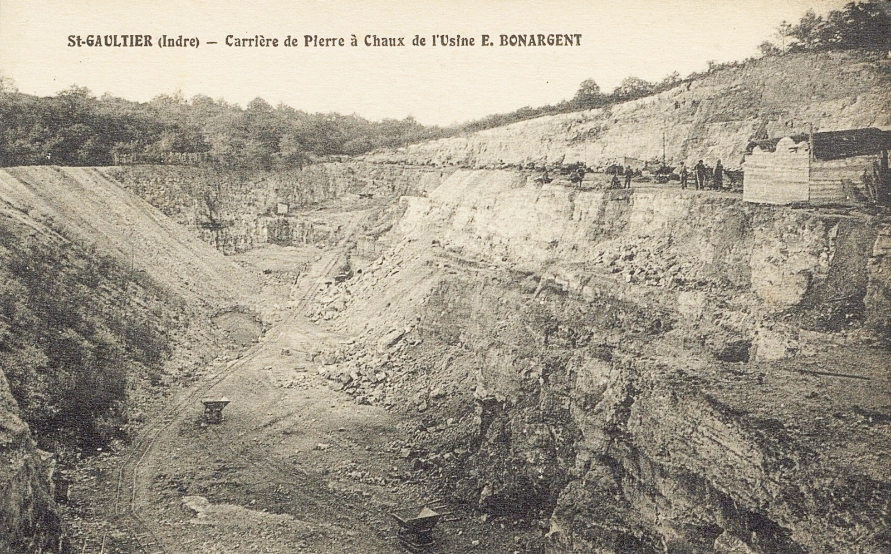

Here’s where Saint-Gaultier gets properly interesting. At the turn of the 20th century, over 300 workers were producing lime in Saint-Gaultier and the neighbouring village of Thenay. The town became one of the most important lime producers in France, and remnants of this industry are visible all over town.

How lime production worked

Lime production requires limestone, fuel, and kilns. Saint-Gaultier had limestone in abundance, the local geology is basically made for it. The Creuse provided transport for the finished product. And the forests provided fuel for the kilns that burned at temperatures hot enough to transform limestone into quicklime.

What you can still see

Walk along the Avenue de Lignac and you’ll see the remains: abandoned kilns, quarry faces, workers’ houses, even bits of the old railway line that carried lime to buyers across France. It’s industrial archaeology in situ, nobody’s turned it into a heritage trail with interpretive panels, so you’re just walking through a town where the bones of the 19th-century economy are still visible in back gardens.

From local company to global giant

The big name in Saint-Gaultier lime was Bonargent. The company operated for 150 years and, thanks to smart decisions in the 1960s by its director Albert Goyon, became one of the cornerstones of the Balhazard et Cotte group. By the turn of the 21st century, Bonargent was part of the Lhoist Group, currently the world leader in lime production!

So this town of 1,800 people was, for a century and a half, part of a supply chain that ended with a global industrial giant. Lhoist still operates a limestone quarry in Saint-Gaultier today, though the lime processing that once employed hundreds is now done elsewhere.

Learning more about the industry

The local historical society has published a book about it: “La chaux, du matériau universel à son histoire à Saint-Gaultier” (Lime, from universal material to its history in Saint-Gaultier). It covers the principles of lime production, the different types of kilns, the transition from artisanal to industrial techniques, and the hard labour of the quarrymen and lime burners.

If you’re in Oulches, a village near Saint-Gaultier, you’ll find restored lime kilns with an interpretive trail. But honestly, just walking through Saint-Gaultier itself gives you a better sense of what this industry meant. It wasn’t a cute heritage site, it was dirty, dangerous work that employed hundreds of people and shaped the town’s economy for generations.

Why lime mattered

The lime went everywhere: agriculture, construction, metallurgy. Every time a French farmer needed to correct soil pH, every time a builder needed mortar, there was a good chance some of that lime came from kilns in Saint-Gaultier.

Fishing the Creuse: pike, carp, catfish, roach

The Creuse through Saint-Gaultier is second-category fishing water, which means it’s not primarily trout (that’s first category). What you get instead is a mixed fishery: pike, perch, bream, roach, carp, zander, and, if you’re lucky or unlucky depending on your perspective, catfish that can weigh 80 kilos.

Eighty kilos. That’s a fish the size of a human adult. Downstream from Le Blanc, the Creuse holds catfish that require serious tackle and determination. They’re not native, they were introduced from Eastern Europe, but they’ve thrived in French rivers to the point where some locals consider them a nuisance. Others consider them the ultimate challenge. Either way, they’re there.

The “parcours de pêche” (fishing trail) in Saint-Gaultier is marked out along the Creuse. It’s open 24 hours, accessible on foot or by road, and you can fish various techniques: fly fishing for chub, dace, and the occasional trout; coarse fishing for roach, bream, and gudgeon; spinning for pike and perch; live bait or dead bait for pike and zander; and bottom fishing for eels.

Fishing permit

You’ll need a fishing permit, available from the Fédération de Pêche de l’Indre or from the tourist office in Saint-Gaultier. The federation also offers free half-day introductory sessions for beginners, which is decent of them.

The stopover on the A20

Saint-Gaultier works as a stopover on the A20 if you’re driving south and want something with character instead of a motorway hotel. It’s also useful if you want a proper town base for exploring the Brenne or the Creuse valley without being isolated. You’ve got shops, restaurants, and facilities within walking distance. Walk up to the church, cross the viaduct for the views, have lunch at Les Chimères, poke around the old town looking for bits of fortification.

It’s not touristy, which depending on your perspective is either brilliant or disappointing. This is a working town that happens to have medieval bones, an interesting industrial past, and good fishing. It won’t be the highlight of your French trip, but it’s properly French, quiet, slightly shabby in places, the sort of town where people actually live.

And the A20’s five minutes away when you’re done.

What to see and do in Saint-Gaultier

- Église Saint-Gaultier and the Priory

The 11th-century Romanesque church sits above the river with proper medieval carvings, look for the donkey playing a lyre on the capitals round the back. - The lime kilns walk (Avenue de Lignac)

Industrial archaeology without the heritage trail polish. Walk along Avenue de Lignac and you’ll see abandoned kilns, quarry faces, and workers’ houses from when 300 people made lime here. - Fishing on the Creuse (Parcours de pêche)

Designated fishing trail along the river. Night carp fishing allowed in marked sections. Peaceful, methodical, proper French river fishing. - The voie verte (old railway line)

Traffic-free cycling path along the former railway. Flat, easy, runs right through town crossing the Creuse on the old viaduct. Good surface, gentle countryside, no tractors trying to overtake you. - The old town and fortifications

Medieval streets, bits of ramparts poking out of gardens, Rue du Cheval Blanc where Henri IV supposedly stayed in 1589. The church bells were sold during a famine, which tells you something about 18th-century priorities. - Friday market

Small weekly market in the town centre. Local produce, cheese, general people-watching. - L’Ilon (the island)

Small island in the Creuse that hosted fishing festivals until the 1990s. There’s an old mill at the tip that produced electricity from 1902. Now it’s just a nice riverside walk. Quiet, bit of local history, decent spot for a sit-down. - Les Chimères restaurant

Worth mentioning because it’s the best place to eat. French cooking done properly, baby grand piano, sometimes live music. On Place de l’Hôtel de Ville. Book ahead at weekends.

Practical information for visitors

- Getting there

Saint-Gaultier’s just off the A20 motorway between Châteauroux and Limoges. From Châteauroux, about 25 kilometres. Easy. No train station, the railway closed decades ago, which is why you can cycle on it. Nearest station is Argenton-sur-Creuse. - When to visit

Spring (April-June) and autumn (September-October) are best. Not too hot, countryside’s lovely, fewer tourists. - Accommodation

You’ll find a decent mix of places to stay: small hotels in the town centre, B&Bs, guesthouses, and self-catering options. Nothing too fancy, but welcoming and comfortable. If you want more space and countryside views, there are gîtes and chambres d’hôtes dotted around the surrounding villages. Book ahead during the book fair in summer, the town fills up fast.