French oysters: The complete guide

I won’t lie, the first time I tried oysters, I didn’t know what to expect. The texture properly surprised me. But already by the second one, I was hooked. That complex taste of the sea is addictive. I find it strange when people just swallow them whole without savouring them. I chew and chew to extract every bit of flavour from these delicacies. And yes, in my books (and most French people), they are for special occasions.

Did you know that half the oysters French people eat all year get consumed between Christmas Eve and New Year’s Day? That’s 4 kilograms per household in less than a fortnight. It’s not a religious thing, though you’ll see oysters on every réveillon table from Brittany to Provence. It’s simply that oysters are what you eat when something matters. And in France, the end of the year matters.

Why French people are obsessed with oysters

Louis XIV had six dozen French oysters delivered to Versailles daily, where he’d slurp them down before breakfast. Napoleon ate them before battles for luck. French philosophers ate them for inspiration, which frankly explains a lot about French philosophy.

These days, oyster consumption is less about divine right. France farms, sells, and eats more oysters than any other European country. French households buy an average of 9 pounds of oysters per year, which sounds reasonable until you realise half that amount gets eaten between Christmas Eve and New Year’s.

Pop-up oyster stalls appear on Paris street corners in December. Every fishmonger has towers of oyster boxes stacked outside. Restaurants swap their regular menus for seafood platters. It’s properly mad.

The tradition has practical roots. Oysters spawn in warm weather, making them less appealing in summer months. Before refrigeration, you could only ship oysters inland safely during cold months. So eating oysters in months with an ‘R’ in their name became the rule. September through April. Sensible.

But there’s also this: the French want festive meals that are deliberately different from everyday life. French oysters tick both boxes. They’re special. They’re not cheap. And when served on a bed of ice with champagne, they look the part.

The two types of French oysters

France grows two types, though you’ll see one far more often than the other.

Huîtres creuses

Cupped oysters

These are the most common French oysters, making up the vast majority of the market. They’re Pacific oysters, originally from Japan, with curved, deeply cupped shells. The French call them creuses or sometimes japonaises.

They arrived in France by accident in 1868 when a cargo of supposedly dead Portuguese oysters was dumped in the Gironde estuary. They flourished. Then in the 1970s, disease wiped out the Portuguese variety, so French oyster farmers switched to Pacific oysters. Now they dominate.

Taste

The creuses have a mild, balanced flavour. Salty but not aggressively so, with a clean finish. They’re what you’ll find at most restaurants and markets.

Huîtres plates

Flat oysters

These native French oysters are more elusive and expensive. They account for only 1-2% of oyster production. They’re called plates or, more romantically, Belons when they come from Brittany.

They’re harder to farm, take longer to mature, and cost significantly more. If you see them on a menu, you’re either in a very good restaurant or paying for the privilege.

Taste

They have a dense, slightly metallic and challenging flavour that’s deeply satisfying. More complex, more lingering, often described as refined and nutty.

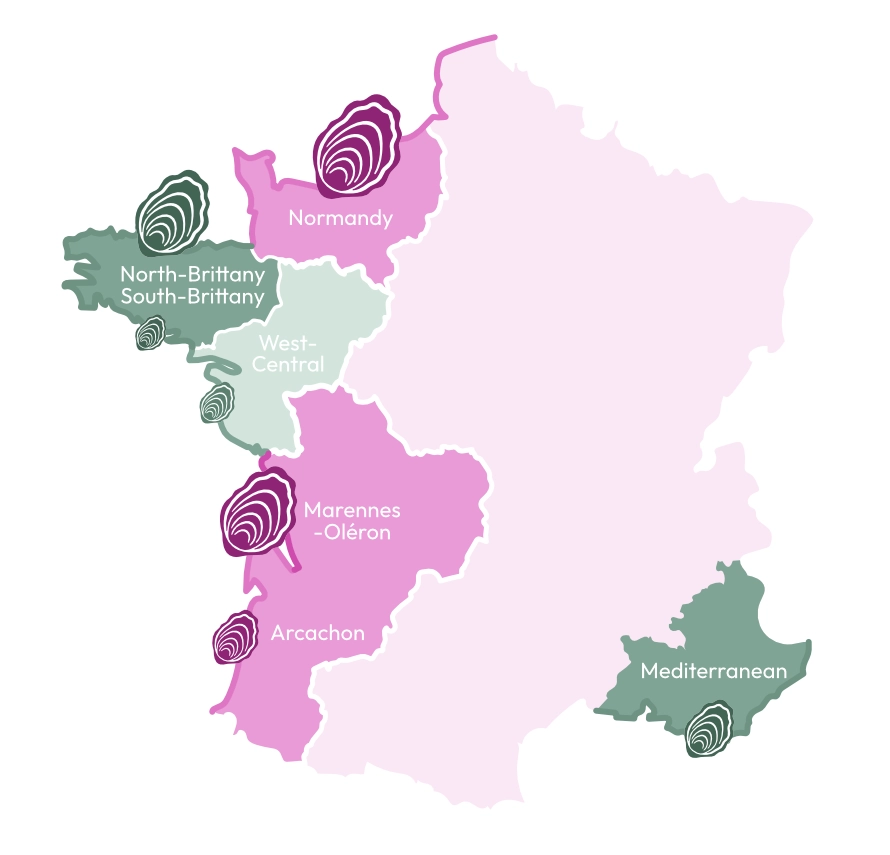

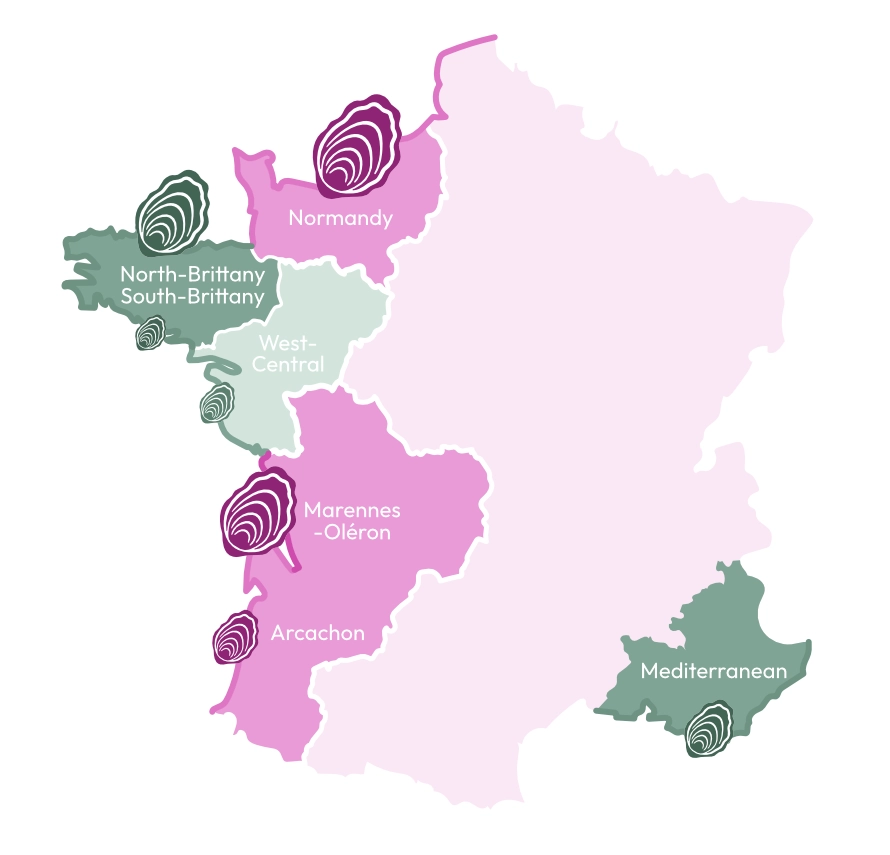

French oyster regions

From north to south, there are seven distinct growing regions: Normandy, North-Brittany, South-Brittany, West-Central, Marennes-Oléron, Arcachon, and the Mediterranean. Each produces French oysters with different flavours, shaped by water temperature, salinity, and what the oysters feed on.

Normandy

Norman oysters grow in cold, nutrient-rich waters with strong tides. The oysters here benefit from the mixing of Channel waters, which brings in plenty of plankton. Less famous than some southern regions, but the quality’s excellent and they’re often better value. The main production areas include the Cotentin Peninsula and areas around the Seine estuary.

Taste

They tend to be plump and meaty with a bold, briny flavour. The region’s known for producing substantial oysters with pronounced iodine notes. These oysters have proper body and a clean, assertive taste that reminds you exactly where they came from.

North-Brittany

This is where Cancale sits, arguably France’s most famous oyster town. North Brittany oysters are raised in parks opposite Mont-Saint-Michel where they benefit from some of the world’s strongest tides. The tidal range is massive, up to 14 metres in some areas. This exposes oysters to sun daily whilst bringing in plankton-rich water. Cancale was declared the official provider of oysters to the royal table of France. These days, you can buy oysters from roadside stalls overlooking the bay, watch them being shucked, and eat them immediately whilst looking at the farms they came from. Other notable areas include Paimpol and the Bay of Saint-Brieuc.

Taste

Firm, supple flesh with a pronounced iodine scent. The result is oysters with intense ocean flavour and excellent texture. All produce oysters with that distinctive, powerful Atlantic character. Worth the trip.

South-Brittany

South Brittany’s waters are slightly warmer and more sheltered than the north, which affects both growth rate and flavour. The region includes areas like the Gulf of Morbihan and the Étel and Belon rivers. The famous Belon flat oysters (huîtres plates) come from here. Belon plates are raised in the ocean for three years, then transferred to the Belon river estuary where fresh and salt water mix. They’re expensive, difficult to find, and absolutely worth trying if you get the chance.

Taste

South Brittany produces softer, rounder oysters than the north. These oysters tend to have a gentler, less aggressive brine with subtle sweetness. Belon plates are those challenging, metallic, utterly distinctive oysters that proper enthusiasts go mad for, with signature mineral complexity and lingering finish.

West-Central

This basin covers the Vendée-Atlantic coast, including the Loire estuary, Noirmoutier, and the Bay of Bourgneuf. The Vendée-Atlantic oyster is produced in several specific areas: the Bay of Bourgneuf at Bouin, the island of Noirmoutier, the Bay of Aiguillon, and around Pornic. The region’s oyster farming history involved several generations of determined producers who mastered very specific local conditions. They’re somewhat underrated compared to more famous basins, but that means better value for equivalent quality.

Taste

The oysters here reveal a balanced taste with firm, crunchy flesh. They’re particularly appreciated by people who want oysters that are neither too briny nor too mild. Each sub-area has slightly different characteristics, but all share that balanced, satisfying quality with good body and a clean finish.

Marennes-Oléron

This is France’s largest and most prestigious oyster-producing basin. What makes Marennes-Oléron special is the claires, shallow clay ponds where oysters spend their final weeks or months. The oysters filter brackish water, sometimes picking up a distinctive green tint from blue-green algae. The grading system is rigorous: Fines de Claire spend at least 28 days in the claires. Fines de Claire Verte are the same but with green colouration (first seafood to receive France’s Red Label in 1989). Spéciales de Claire spend at least two months at lower density. Pousse en Claire spend four to eight months at just 5 oysters per square metre, the aristocracy of French oysters.

Taste

This maturation gives Marennes-Oléron oysters a flavour of “marine lands” and a rich taste that lingers in the mouth. Fines are lean, balanced, refined. Spéciales are plumper, richer, more substantial. Pousse en Claire double their weight during maturation, not cheap, but if you want to understand what the fuss is about, try them once. This region produces oysters that are considered the benchmark for quality and refinement throughout France.

Arcachon

The Arcachon Basin, near Bordeaux, is France’s leading breeding basin. It provides most French oyster farms with natural spat (baby oysters) that are then sent to other regions. But Arcachon also produces finished oysters. The basin has several distinct growing areas, Cap-Ferret and Île aux Oiseaux (Bird Island) being the most notable. The town of Arcachon is also a brilliant place to eat oysters, with dozens of cabanes (oyster shacks) lining the waterfront where you can eat fresh oysters with bread, butter, and white wine whilst watching the tide.

Taste

Oysters here have strong personality and distinctive character. At Cap-Ferret, you’ll taste delicate, refreshing scents of vegetables and citrus. At Bird Island, the oysters have vegetal and mineral aromas with more depth. Arcachon oysters tend to be meaty with a rich, full flavour. They’re less refined than Marennes-Oléron varieties but have more immediate impact. Some people prefer this directness.

Mediterranean

Mediterranean oysters are farmed mainly in the Étang de Thau lagoon near Sète and Bouzigues, though also in other locations like the Étang de Leucate. No tides in the Med, so they use a different farming method, young oysters are glued individually to ropes with cement (called the “collage” technique). The ropes hang vertically in the water, and the oysters grow faster than their Atlantic cousins because they’re always feeding. The Thau lagoon has been farming oysters since Roman times. The water quality is exceptional, grade A, which means oysters can be consumed immediately after harvesting.

Taste

Firm and melting with a slight hazelnut flavour and fine, delicate flesh. These French oysters are milder and rounder than their Atlantic cousins, with soft flesh and hints of hazelnut. Still briny but more gently so. Some people find them less interesting than Atlantic varieties, but if you prefer a subtler oyster, Mediterranean ones are excellent. Worth trying if you’re in Languedoc, though traditionalists often maintain that proper oysters come from the Atlantic.

Understanding French oyster sizes

French oysters are numbered 000 to 6. Here’s the confusing bit: the smaller the number, the larger and meatier the oyster. So No. 000 oysters are enormous. No. 6 oysters are tiny. No. 3 is the most commonly served size in restaurants. It’s balanced in flavour and manageable, making it a good starting point. No. 1 or 2 are larger and often more intensely flavoured. They’re better suited to those already comfortable with the texture and taste. If you’re new to French oysters, start with No. 3 or 4. They’re not overwhelming, you can actually taste the different regional characteristics, and they’re what most French people order.

The grades: fines, spéciales, and pousse en claire

You’d think that was all, but there is more. They also grade them by how they’ve been finished.

| Grades | Taste and Texture |

| Fines | Fines are for those who prefer a less fleshy oyster. They’re finished for several weeks in shallow clay ponds where they acquire superior shell quality. They’re lean, with balanced flavour and more water content. Fines de claires spend 28 days in the claire. Lean and balanced. |

| Spéciales | Spéciales de claire are French oysters selected for their larger size and regular shape. They’re matured in claires for several weeks. They are plumper than the fines de claires. More flesh, richer taste, longer finish. Spéciales de claire are highly sought-after and expensive. These are very privileged oysters, fattened in areas with no more than ten oysters per square meter for at least two months. |

| Fines de Claire Verte | Fines de claires vertes were the first seafood product awarded the Red Label in 1989. This indicates superior quality with a nice round shell and striking green colour. The green tint comes from algae in the claires. It’s a mark of quality, not something wrong. |

| Pousse en Claire | The aristocracy of French oysters. Pousse en claire oysters are raised with only five others per square meter. They may be fattened for four months. Some stay even longer, up to eight months. These also have a Red Label. They’re the top-of-the-range Marennes-Oléron French oysters. Whilst other varieties are only matured in the claire, these are bred there. They’re not cheap. But if you want to understand what the fuss is about, try them once. |

The Christmas and New Year tradition

A typical French household buys 9 pounds of oysters per year. Half that quantity is enjoyed between Christmas Eve and New Year’s Day. This is a relatively recent tradition, shaped by two factors. First, France is the number one European producer of oysters. Producers have promoted regular consumption to support the industry. Second, French oysters fit perfectly into French ideas about festive eating.

The meal itself is called “le réveillon”. It’s eaten on both Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve. The big tradition is to serve oysters as an appetizer, with a glass of French champagne, of course.

You’ll see them everywhere in December. Pop-up oyster stalls literally litter city streets leading up to the holidays. Fishmongers shuck oysters in front of customers. Restaurants display towers of French oysters on ice. Many French people believe that without oysters, there is no feast. The new year can be affected negatively. Bit dramatic, but this is France.

How to buy French oysters in the UK

Waitrose

Waitrose stocks fresh oysters at their fish counters, including No. 1 size options like the Isle of Mull oysters. Their counters are now ASC-certified, featuring oysters that meet strict environmental and social standards. They stock Loch Fyne oysters (Scottish, not French, but properly good).

Specialist fishmongers

Better fishmongers will have French oysters in season, particularly in December. Ask specifically for Marennes-Oléron or other French varieties. Many fishmongers can order them with a few days’ notice if they don’t stock them regularly. Online fishmongers also stock oysters. Delivery charges make small orders expensive. Worth it if you’re buying for a proper occasion.

What to look for

If the shell is slightly open and doesn’t close when tapped, throw it away. If it feels hollow or unusually light, it’s probably empty. If it smells sour or strong, definitely not safe to eat. French oysters should smell clean and ocean-fresh. The flesh should look shiny, firm, and sitting in a bit of clear, salty water. If it looks dry or dull, give it a miss.

Buy them as close to when you’ll eat them as possible. Oysters will keep up to 7 days after harvesting. But it’s recommended to buy them 1 to 2 days before serving, or even the same day if possible.

Storing French oysters at home

Oysters are alive. They breathe and need both humidity and cool air. If they’re sealed too tightly or left somewhere warm, they’ll die quickly and become unsafe to eat.

Keep them in their box. Remove any plastic wrap. Cover with a slightly damp towel. Store somewhere cool between 5-10°C. Not the warmest part of your fridge, but not freezing either.

Store them cup-side down so they don’t lose their liquor. Never freeze oysters. Freezing kills them and they become inedible and toxic.

Opening French oysters: tools and technique

Opening oysters without professional help takes practice. But with the right tools and method, it’s perfectly manageable.

The essential tool: an oyster knife

You absolutely need a proper oyster knife. Don’t try this with a regular kitchen knife or paring knife. You’ll either break the knife, damage the oyster, or stab yourself. Possibly all three. An oyster knife has a short, thick blade, usually about 7-8cm long. The blade is blunt, not sharp. It’s designed for leverage and twisting, not cutting.

Other useful tools

A thick tea towel or folded cloth is essential. You’ll use it to protect your hand whilst holding the oyster. Some people use a proper oyster glove (a chainmail or Kevlar glove), which is safer but not strictly necessary if you’re careful. De Buyer (culinary French brand) makes a silicone oyster mitt specially for opening oysters.

The technique

Step 1

First, scrub your oysters under cold running water. Get rid of any sand, mud, or bits of shell. Pat them dry with a clean towel.

Step 2

Find the hinge at the pointed end. This is where the two shells meet and create a small gap. Take your oyster knife and position the tip at the hinge, angled slightly upwards.

Step 3

Now comes the tricky bit. You need to wiggle the knife tip into the gap whilst applying steady pressure. Push and twist gently. You’re looking for the moment when the knife tip pops through the hinge. You’ll feel it give.

Step 4

Once you’re inside, don’t pull the knife out. Instead, twist the knife 90 degrees to pry the shells apart slightly. You’ll hear a small crack.

Step 5

Now slide the knife blade along the inside of the top (flat) shell. Keep the blade flat against the shell. You’re cutting through the adductor muscle that holds the two shells together. Run the knife all the way around until the top shell comes free.

Step 6

Lift off the top shell. You should see the oyster sitting in its liquor in the bottom shell.

Step 7

Finally, slide your knife under the oyster meat to detach it from the bottom shell. Be gentle. You don’t want to tear the flesh or spill all the liquor.

Common mistakes

- Putting the knife in the wrong place is the biggest error. If you try to force the knife in at the side rather than the hinge, you’ll crush the shell and get fragments everywhere.

- Using too much force is another problem. This isn’t about brute strength. You need to find the right angle and wiggling the knife until it slips through. Steady pressure beats aggressive jabbing.

- Lifting the top shell before cutting the adductor muscle means you’ll rip the oyster. Always cut the muscle first.

Safety tips

Always use protection. Always. Even experienced shuckers use protection because knives slip. Work slowly, especially when you’re learning. Opening a dozen French oysters might take 20 minutes at first. That’s fine. Speed comes with practice. If an oyster is particularly stubborn, set it aside and try another. Sometimes you get a difficult one. Don’t fight it to the point where you’re likely to hurt yourself. Keep your other hand (the one not holding the knife) behind the blade, never in front of it.

If this all sounds too much

Many fishmongers will shuck French oysters for you if you ask. Some charge a small fee, others do it for free if you’re buying a decent quantity. The thing is that shucked oysters need eating within an hour or two. You can’t prepare them in the morning for an evening party. But for immediate consumption, it’s a brilliant option.

How French people actually eat oysters

The classic French approach is simple, and my personal favourite way to really enjoy the taste of oysters. French oysters are on ice, wedge of lemon, maybe some shallot vinegar (mignonette), good bread, salted butter, and champagne or a crisp white wine.

Mignonette Sauce

Red wine vinegar with finely minced shallots and black pepper. That’s it. Mix it an hour before serving so the shallots soften slightly. Some people add a tiny splash of lemon juice. You don’t drown the oyster in it. Just a few drops to cut through the brine.

Accompaniments

Thin slices of rye or sourdough bread with proper salted butter. French people often alternate between oysters and buttered bread, which sounds odd but works brilliantly. Lemon wedges, always. Some people use them, some don’t. Personal choice.

What to drink with French oysters

Champagne is traditional for “réveillon”. But for everyday oyster eating, French people drink Muscadet, Sancerre, Chablis, or other bone-dry whites. The wine should be cold, crisp, and not too aromatic. You want it to complement the oysters, not compete with them.

Over to you

Not everyone likes oysters. Some people try them once, hate the texture, and never go back. That’s fine. Life’s too short to eat things you don’t enjoy just because they’re considered sophisticated.

But if you’re curious, French oysters are the ones to try. The variety of flavours between regions is genuinely interesting. Cancale oysters taste nothing like Mediterranean ones. The grading system, whilst confusing, does mean something. And the whole tradition of eating them at Christmas feels properly special without being pretentious. And yes, have them with champagne if you can. Some clichés exist for good reasons.

What kind of French oysters have you tried, or is this all new territory?

If you’ve never had them, December’s the perfect time to start. Most fishmongers stock them in the run-up to Christmas, and the quality’s brilliant. Start with a half dozen No. 3 fines de claire. Worst case, you’ve spent £15 discovering oysters aren’t for you. Best case, you’ve found a new obsession.

If you’re already converted, I’d love to know which region you rate. Are you Team Cancale with those proper briny Atlantic oysters? Or do you prefer the more refined Marennes-Oléron varieties? And have you tried the Mediterranean ones, or do you think they’re a bit too mild?

Let me know in the comments what you think of French oysters, or if you’ve got questions about them. Always happy to talk about oysters. Possibly too happy.

Just so you know, a few links here earn us a commission. Doesn’t cost you anything extra, and we only link to things that are actually worth your time.