French Butter: What makes it different (and actually better)

There’s a moment that happens when you first try proper French butter. You’re spreading it on a bit of baguette, probably still warm, and you realise everything you’ve been eating until now has been a lie. French butter just taste different. It’s richer, creamier, sometimes slightly tangy. It’s got actual flavour, not just fattiness. And once you’ve had it, going back to anything else feels like a punishment.

So what makes French butter special? Why does France produce butter that costs three times as much and is worth every penny? And which ones should you actually buy? Let’s start with why French butter exists at all.

How France became obsessed with butter

France wasn’t always butter country. For centuries, the Mediterranean south cooked with olive oil whilst the northern regions used lard and animal fats. Butter was peasant food, something you made because you had cows and needed to preserve excess cream.

The Catholic Church

The Catholic Church changed everything. During medieval times, the Church banned butter during Lent. Forty days without butter sent northern French regions, particularly Normandy and Brittany, into mild chaos. These areas couldn’t grow olive trees, and cooking with lard during Lent felt wrong. So they petitioned Rome. And Rome, in a move of spectacular pragmatism, agreed to allow butter during Lent in exchange for donations to build Rouen Cathedral. The “Butter Tower” still stands today, literally funded by people’s desperate need for butter.

From necessity to luxury

By the 17th century, butter had moved from necessity to luxury. French cuisine was developing its identity, and butter became central to it. The Norman and Breton dairy regions perfected production methods. Royal courts demanded specific types. Butter became something you could be snobby about.

Then came AOC designations in the 20th century, Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée, the same protection system used for wine and cheese. Because French people cannot do anything without making it official. Certain butters gained protected status, meaning they had to be made in specific regions using specific methods with milk from specific cows eating specific grass. This was France deciding that butter mattered enough to regulate it like Champagne.

What makes French butter different

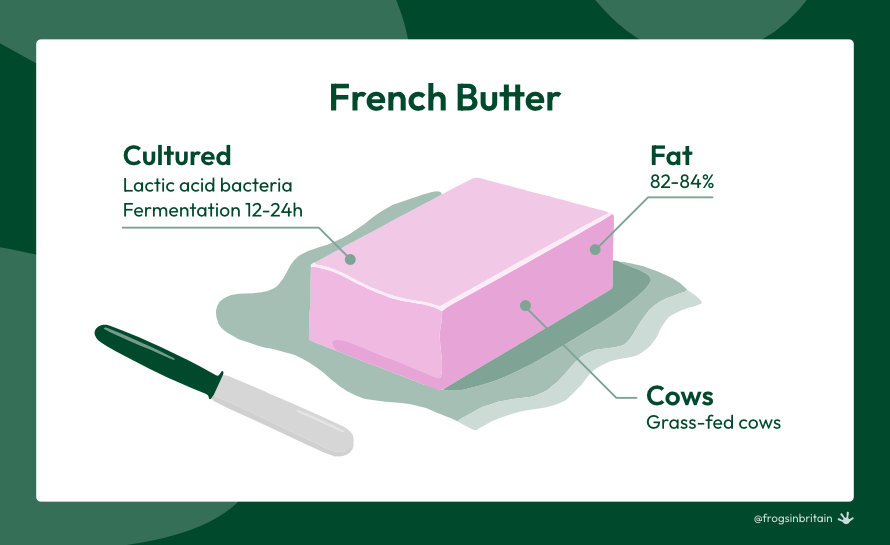

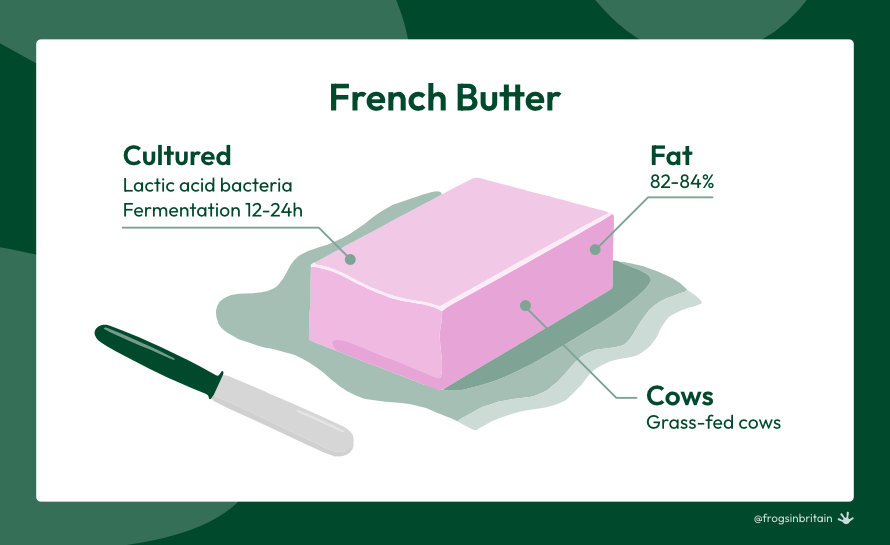

Fat content

The difference seems subtle. French butter has a fat content of 82-84%, compared to 80% in most British and American butters. That extra 2-4% sounds minor until you taste it. More fat means richer flavour, better texture, and yes, it melts differently on your tongue. But fat content alone doesn’t explain it.

Cultured

Most French butter is cultured. After pasteurisation, producers add lactic acid bacteria to the cream and let it ferment for 12-24 hours before churning. This develops complex, slightly tangy flavours, similar to the difference between regular milk and buttermilk, or between mass-produced yoghurt and the proper stuff.

British and Irish butter is typically sweet cream butter, made from fresh cream without fermentation. It’s cleaner, more neutral, which is fine if you want butter that disappears into your cooking. French butter doesn’t disappear. It announces itself.

Cows

The other factor is the cows. French butter regulations often specify that milk must come from cows that graze on grass for a minimum number of days per year. Grass-fed cows produce milk with different fat composition and more beta-carotene, which gives the butter a deeper yellow colour. You can actually see the quality.

Types of French butter

Walk into a French supermarket and you’ll find an entire refrigerated section dedicated to butter, which personally I just love. Here’s what you’re looking at.

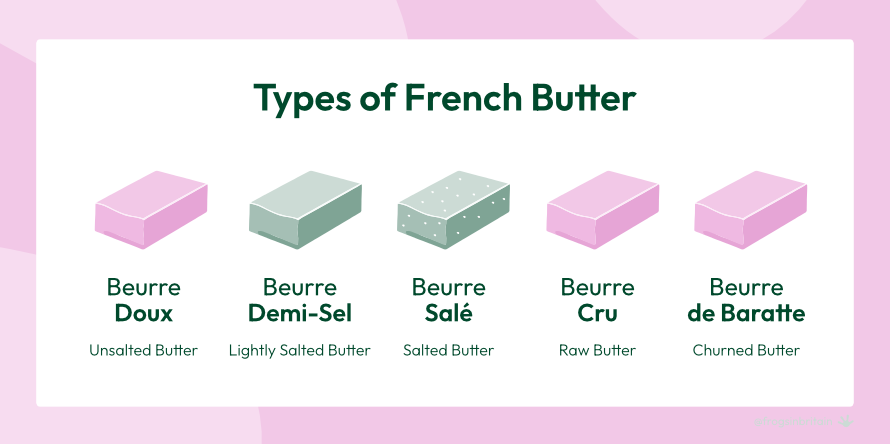

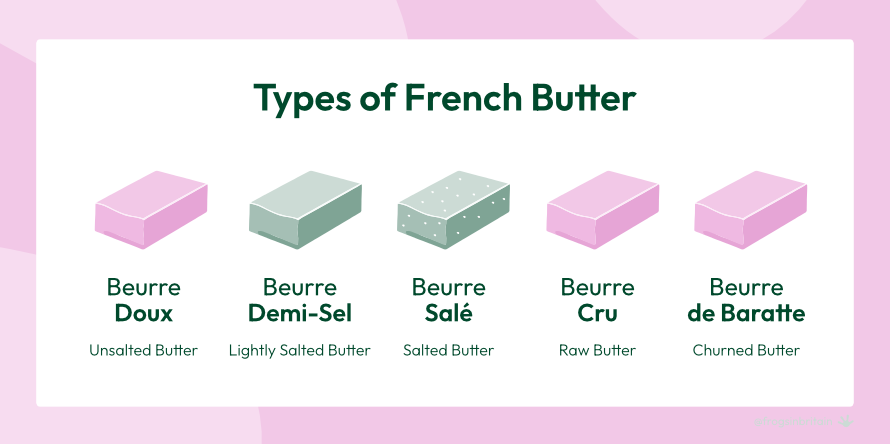

Beurre Doux (Unsalted Butter)

The default in most of France, particularly in the south. This is what French recipes assume you’re using unless stated otherwise. It’s pure butter flavour without salt interfering. Baking almost always requires unsalted butter because you want control over salt levels in your pastry.

The best unsalted French butters have a clean, sweet cream flavour with that characteristic slight tang from culturing. They’re brilliant on good bread where you want to taste the butter itself, not just saltiness.

Beurre Demi-Sel (Lightly Salted Butter)

The compromise butter. Contains 0.5-3% salt, which is less than you’d think. This is popular across France but especially in regions that aren’t quite as militant about their butter preferences as Brittany.

Demi-sel works brilliantly for everyday cooking and spreading. The salt enhances the butter’s flavour without overwhelming it. It’s what I keep in my fridge most of the time, because it’s versatile enough for both cooking and eating straight on bread.

Beurre Salé (Salted Butter)

This is Brittany’s butter, and Bretons are very serious about it. Proper beurre salé contains at least 3% salt, often more. Sometimes you can see salt crystals in it.

Salted butter is contentious. Some French chefs refuse to use it. Others, particularly in Brittany, use nothing else. It’s traditional, it keeps longer without refrigeration (important historically), and on warm bread with flaky salt crystals, it’s genuinely incredible.

The salt debate gets heated. Normandy and Brittany have been arguing about butter superiority for generations. Normandy produces more butter. Brittany insists theirs is better. Both are right and wrong, depending on what you’re making.

You can find the French butter with sea salt crystals at Waitrose! This butter comes from Brittany and made to a classic Breton recipe.

Beurre Cru (Raw Butter)

Made from unpasteurised cream, which is legal in France under strict conditions. This is the butter equivalent of raw milk cheese, more complex flavours, more variation between batches, and definitely more expensive.

Beurre cru tastes intensely of wherever it came from. Spring butter tastes different from autumn butter because the cows ate different grass. You can detect “terroir”, which sounds pretentious until you try it and realise you actually can taste the meadow.

It’s not widely available outside France because raw dairy products face stricter export regulations. If you find it, buy it. Use it on bread or radishes or boiled new potatoes, anything where butter is the main event.

Beurre de Baratte (Churned Butter)

Traditionally churned in wooden barrels rather than modern continuous churns. This is slower, produces smaller batches, and creates a different texture, slightly less smooth, more artisanal.

Whether you can actually taste the difference is debatable. Whether it’s worth the extra cost depends on how much you care about traditional methods and supporting small producers. I’d argue yes for special occasions, but I’m not churning through £8 butter on a Tuesday morning’s toast.

The protected butters with AOP status

Some French butters are so regionally specific they’re legally protected. These are the ones worth knowing about.

Beurre de Charentes-Poitou (AOP)

Made in the Charentes-Poitou region from cows grazing on Atlantic coastal pastures. The milk is collected and churned within 48 hours, and the butter must be cultured for at least 12 hours.

Échiré is probably the most famous Charentes-Poitou butter. It comes in the distinctive wooden basket and costs a small fortune. Is it worth it? Absolutely. It’s sweet, creamy, with a long finish that lingers. Use it on good bread or warm croissants where you’ll actually appreciate it.

Lescure is another Charentes-Poitou butter that’s more widely available and slightly less expensive. Still excellent.

Beurre des Deux-Sèvres (AOP)

Less well-known internationally but highly regarded in France. Made in the Deux-Sèvres department from milk collected within 48 hours and cultured for at least 15 hours.

This butter tends to be more intensely flavoured than others, tangier, more pronounced fermented notes. It divides opinion. Some find it too strong for delicate applications. Others think it’s perfect for cooking where you want butter flavour to shine through.

Beurre d’Isigny (AOP)

From the Isigny-sur-Mer region of Normandy, where cows graze on salt meadows influenced by tides from the English Channel. The maritime climate and specific grasses give Isigny butter a subtle hazelnut flavour.

Isigny Sainte-Mère is the main producer. Their butter is smoother than Échiré, less tangy, with a rounder flavour profile. It’s exceptional for pastry because it has good plasticity, it stays workable when cold, which matters for laminated doughs like croissants and puff pastry.

You can find the Isigny Ste Mere unpasteurised salted butter at Waitrose! From cows grazed on the lush grass of Normandy’s mineral-rich salt marsches. Traditionally slow churned and slowly cultured for a minimum of 12 hours.

Beurre de Bresse (AOP)

From the Bresse region in eastern France, known primarily for its chickens but also producing distinctive butter. Made from milk from Montbéliarde, Simmental, or Tarentaise cows grazing on Bresse pastures.

Bresse butter is golden yellow with a firm texture and assertive flavour. It’s less commonly exported but worth trying if you find it.

How French butter is actually made

The process matters because it affects flavour. First, milk is separated to extract cream. This cream is pasteurised (except for beurre cru) to kill unwanted bacteria. Then comes culturing, lactic acid bacteria are added and the cream ferments at controlled temperatures for 12-24 hours. This is where French butter develops its characteristic tang.

After fermentation, the cream is churned. Traditional methods use wooden barrel churns that tumble the cream until fat globules clump together, separating from buttermilk. Modern industrial methods use continuous churns, which are faster and more efficient but produce slightly different texture.

Once butter forms, it’s washed with cold water to remove residual buttermilk, then kneaded to achieve the right consistency. Salt is added at this stage if making salted or lightly salted butter. Finally, it’s shaped, wrapped, and refrigerated.

The entire process from milking to packaged butter takes about 48-72 hours for quality producers. Industrial operations can do it faster, but faster isn’t better with butter.

What to actually use French butter for

French butter costs more, so use it where you’ll notice the difference.

On bread

Obviously. Warm baguette, good butter, flaky salt. This is where cultured butter shows what it can do. It’s also delicious for Pain Perdu (eggy bread). The slight tang complements bread’s sweetness, and the richness coats your mouth in a way standard butter simply doesn’t.

Finishing dishes

A knob of good butter stirred into soup, risotto, or pasta sauce at the end transforms it. French chefs do this constantly, mount with butter, they call it. The butter emulsifies into the liquid, adding richness and gloss. Use cultured butter and you also get subtle complexity.

Pastry

French butter’s higher fat content and good plasticity make it excellent for puff pastry, croissants, and laminated doughs. The butter needs to stay solid enough to create distinct layers without melting too quickly. Isigny butter is particularly good for this.

Butter sauces

Beurre blanc, hollandaise, and similar emulsified sauces benefit from quality butter. You’re using a lot of it, and it’s the main flavour, so cheap butter makes cheap sauce. Use unsalted so you can control seasoning precisely.

Radishes

French bistro classic, room temperature butter, radishes, flaky salt. Sounds simple because it is. The butter mellows the radish’s peppery bite whilst the radish cuts through the butter’s richness. Use salted butter if you’re feeling Breton about it.

Baked potatoes

Controversial opinion, French butter is wasted on baked potatoes. You need enough butter that the cost becomes absurd, and the potato’s fluffiness masks subtle butter flavours anyway. Use decent butter, sure, but save your Échiré for something else.

Sautéing

Butter burns easily, so most cooking uses butter combined with oil or clarified butter. That said, finishing green vegetables in butter (technically called “glacer“) is brilliant with good butter. The vegetables pick up nutty, caramelised butter flavours. Try it with this green beans recipe, asparagus, or Brussels sprouts.

Cakes and biscuits

This is where I’ll lose some people, you can taste the difference between regular butter and French cultured butter in cakes and biscuits, but whether it’s worth the cost is debatable. For special occasion cakes, yes. For Tuesday night biscuits, probably not.

The butter you actually see in France

French people don’t exclusively use £8 artisanal butter any more than British people exclusively use grass-fed Aberdeenshire butter from farm shops.

Most French households keep a commercial cultured butter from brands like supermarket’s own brands, Elle & Vire, or Paysan Breton. These are perfectly good butters, properly cultured, with decent fat content. They’re what goes into most French home cooking.

The fancy butters, Échiré, Bordier, Beurre d’Isigny, are for special occasions or for people who care enough about butter to spend money on it. Which is more people in France than in Britain, admittedly, but it’s still not the daily butter.

French supermarkets also sell cheap butter, which is basically identical to cheap British butter, industrially produced, often from reconstituted cream, no culturing, minimum fat content. French people buy this too, despite what the marketing wants you to believe.

The difference is that even mid-range French butter is cultured, which means baseline French butter is simply better than baseline British butter. Not because French cows are magic, but because culturing became standard practice in France and never did in Britain or Ireland.

Storing and using French butter

French butter’s higher fat content and cultured nature mean it behaves slightly differently from standard butter.

Storage

Keep it refrigerated, obviously. But take it out 30-60 minutes before using so it comes to room temperature. Cold butter doesn’t spread well and won’t cream properly for baking. French butter especially, because it’s richer, benefits from being soft.

Butter absorbs smells easily, so keep it wrapped or in a covered butter dish. Don’t store it next to onions or blue cheese unless you want onion-cheese butter, which frankly sounds interesting but probably isn’t what you’re after.

Butter dish

Le Creuset Stoneware Butter Dish holds standard 225-250g butter blocks. Premium stoneware with chip-resistant enamel finish. Retains cool temperatures longer in summer. Includes 10-year Le Creuset guarantee.

Freezing

Butter freezes well for up to six months. Wrap it tightly to prevent freezer burn. This is useful if you’ve bought expensive butter on sale or brought some back from France. Defrost it slowly in the fridge.

Butter bells

Those ceramic French butter bells that keep butter spreadable without refrigeration work brilliantly with salted butter. The salt acts as a preservative. They’re less reliable with unsalted butter in warm weather, your butter might go rancid. In winter, fine. In summer, less so.

Butter bell

French-inspired butter keeper uses water-seal technology to maintain fresh, spreadable butter at room temperature for weeks without refrigeration. Holds 125g butter, crafted from premium New Bone China.

Butter snobbery and whether it’s justified

Right, let’s address this directly: is expensive French butter actually better, or is it just successful marketing? Having tested more butters than any reasonable person should, I can confirm it’s both.

The quality difference is real

Fancy French butter tastes noticeably better than supermarket butter. The texture is smoother, the flavour more complex, the finish longer. On good bread where butter is the main attraction, the difference is obvious.

But diminishing returns apply. The jump from cheap butter to decent cultured butter is massive. The jump from decent cultured butter to premium AOC butter is real but smaller. The jump from premium butter to ultra-premium artisanal butter is subtle enough that you might not notice it in a blind tasting.

Context matters

Premium butter on bread? You’ll taste it. Premium butter in cookies? Maybe. Premium butter in a beef stew? You’re wasting your money. The snobbery exists, though. Some French people are insufferable about butter, refusing certain brands, insisting on specific regions, arguing about salt content like it’s a moral issue. We’ve never bought margarine, and we never will. Same goes for anything labelled “light” or intensely processed. We’d rather have no butter.

The practical approach

Buy what fits your budget. Don’t feel guilty about using regular butter for most things and saving the good stuff for when it matters. But do try proper French butter at least once. Because once you know what butter can taste like, you’ll never quite be satisfied with mediocre butter again.

Just so you know, a few links here earn us a commission. Doesn’t cost you anything extra, and we only link to things that are actually worth your time.